10 September 2017

Botanical wonders in Warrington

Tracking Kew’s Victorian networks leads to exciting discoveries.

Kew's Mobile Museum Project

As part of Kew’s Mobile Museum research project, which is looking into the global circulation of objects into and out of Kew’s Museum of Economic Botany, we recently got in touch with Warrington Museum, in the north of England. We know from our own records that Kew sent many objects there in the late 19th century. An enquiry to Warrington collections officer Craig Sherwood told us that many of the objects from Kew were still in the collection and a number of them were still on display. Armed with this information, we set off from Euston Station on a mission to reconnect our shared histories.

Importance of regional museums

The Mobile Museum project is working with museum partners from around the world, from Glasgow to Melbourne. This global interaction is a vital element of the project, yet the role of regional British museums is always in our sights. Museums, particularly those located in busy ports and industrial cities like Warrington, have always been active in collecting and displaying economic botany objects, which are things made out of plants that humans use, such as baskets for collecting food or water.

The Botanical Gallery

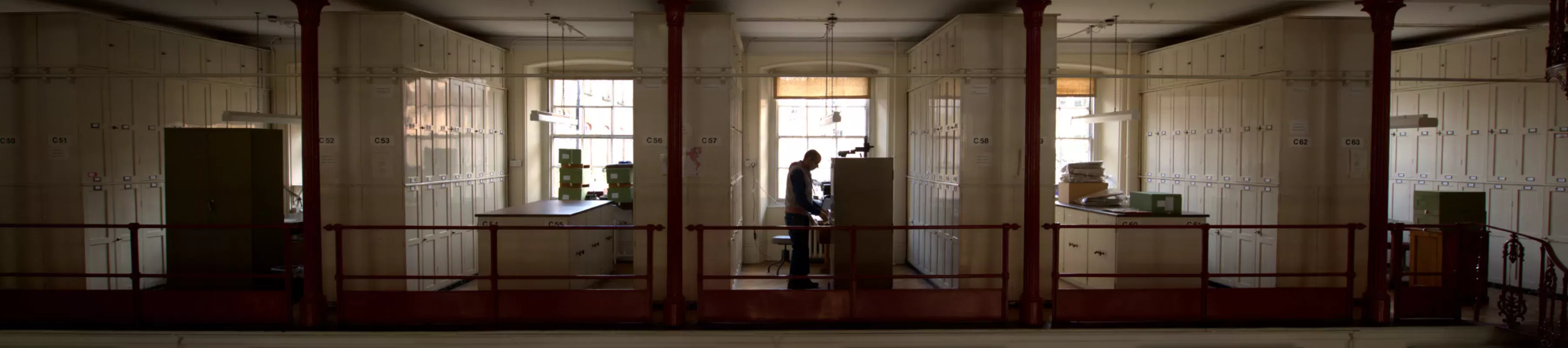

Plants have formed part of Warrington’s museum collection from the beginning, but in the 1880s the emphasis shifted from herbarium specimens (pressed plants) to economic botany (useful plants). As the excellent local history gallery in the Museum makes clear, many local industries such as tanning, weaving and chemical manufacture depended on plants. In 1931, a dedicated Botany Gallery was installed, and this remains almost intact after sensitive restoration in the 1990s.

Stepping onto the balcony is a rare opportunity to experience what it must have been like in Kew’s Museum of Economic Botany in its heyday before its closure in 1960 – in fact it’s like a time machine for historians. The cases are densely packed with fibres, dyes, foods and much else, many sent from Kew’s collections.

The Duke of Edinburgh’s barkcloth

With the help of Craig, we explored some of the Kew objects to be found in Warrington’s reserve collections. Our eye was immediately caught by three pieces of bright yellow barkcloth (cloth made from the bark of a tree), very similar to those at Kew collected by the then Duke of Edinburgh, Prince Alfred, in Tahiti in 1869. He was given these pieces by Tahitian leaders during his visit on the ship HMS Galatea. We know that the Prince gave 82 garments from the Pacific to Kew; so far we have only located 30 at Kew and other museums. We can now make that 33.

Barkcloth, or tapa as it is known locally, is hugely important in the Pacific. Usually made from the inner bark of the paper mulberry tree (Broussonetia papyrifera), it was both a useful material and highly symbolic. Together with colleagues at the University of Glasgow and the Smithsonian Institution, we will be evaluating these new (to us) finds, which are of great importance to contemporary Pacific islanders.

Mysterious baskets

Beth Wilkey, our project’s data officer at Kew, turned detective to track the origins of some of the baskets at Warrington. Some were straightforward, such as determining that a carrying basket labelled as wicker was actually made from esparto grass (from southern Europe / north Africa).

Another basket at Warrington looks almost identical to a basket still at Kew, collected in Kashmir by Surgeon-Major J. E. T. Aitchison before 1873. Though there is no record of the basket being transferred from Kew to Warrington, it is surely part of the same collection.

A concluding thought

Warrington is just one of at least 40 museums in the UK that were sent economic botany objects from Kew. It is becoming clear that many of these objects have survived and been well cared for over the last 150 years. As our project continues, we will be exploring more of the UK’s regional museums and look forward to finding equally amazing objects, and tracing their past.