14 December 2022

Tackling ash dieback at Wakehurst

10 years since ash dieback was first discovered in the UK, we're closing our 150-acre Loder Valley Nature Reserve to carry out a major felling operation.

Ash (Fraxinus excelsior) is one of Britain’s 32 native species of trees. Ash trees are a vital part of the ecosystems in our woodlands and hedgerows as well as a durable wood found in all our homes.

But they’re under threat.

Ash dieback fungus, or Hymenoscyphus fraxineus, is a highly infectious, devastating disease, first discovered in 1992 in Europe. It spread quickly and was officially discovered in the UK in 2012, but evidence shows that ash dieback has been in the UK since 2002.

Diseased trees pose a risk to visitors so our experts will be working across the 150-acre Loder Valley to prevent trees and branches from falling over public paths.

Spotting the signs

The fungus blocks water and nutrients moving in the tree's vascular system, causing a restriction in water movement that leads to significant leaf loss and the dieback in the crown of the tree itself.

The symptoms of ash dieback include:

- Diamond-shaped dark lesions or cankers in the bark

- Black, shrivelled and wilted leaves and shoots in the summer

- Brown stalks and veins

- Mature trees display dieback of twigs and shoots in the crown. Dense clumps of foliage may be seen on branches where recovery shoots are produced

- In late summer and early autumn (July to October), small white fruiting bodies can be found on blackened leaf stalks in damp areas of leaf litter.

Did you know?

Ash dieback is the most significant new tree disease to impact the UK in the last 60 years, since Dutch elm disease.

The importance of ash trees

We rely on ash more than we know.

Its durability and malleability make it a great material for building tools, firewood and beautiful furniture, which you might’ve spotted at our Westwood View Point.

Ash is fundamental to a healthy ecosystem, providing food and homes for a multitude of species, including mammals, birds and insects. The dappled cover it provides allows enough light to allow ground plants like moss to flourish.

Versatile ash trees are skilled at adapting to different soils and climates, which has proven useful for major tree planting schemes.

The practical costs of managing ash dieback, and loss of environmental services such as air purification and flood prevention, also pose a huge financial burden on British society. One study in 2019 has estimated the full economic cost could be as high as £15bn in Britain.

What is being done about it?

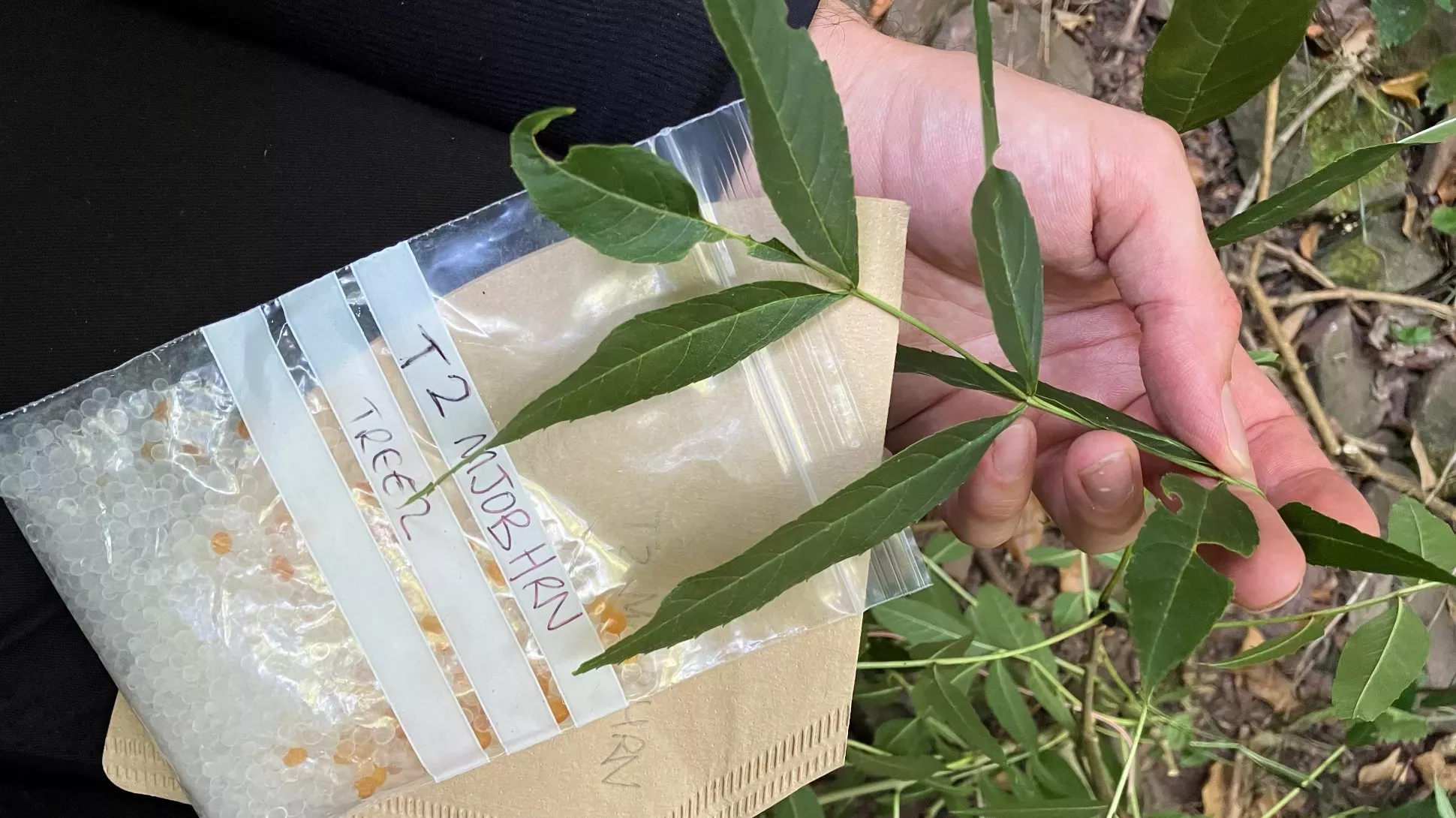

At Wakehurst, we’re bringing together a unique blend of horticulture and science to tackle ash dieback. Our scientists have also been out in the field collecting tree seeds, cuttings and DNA samples from resilient species.

Our Millennium Seed Bank is home to the most important collection of genetically diverse ash seed and our researchers are exploring how they can generate a new population of resilient ash with their seed collections.

Kew scientists are contributing to the Living Ash Project, a major collaboration alongside Future Trees Trust, Fera and Forest Research, funded by Defra. In 2021, Kew scientists began a series of trials to improve ash propagation techniques using cuttings. If successful, the project could lead to the regeneration of Ash trees in the UK landscape, restoring biodiversity and wildlife habitats.

Through pioneering research, we've discovered correlations between genetic variants in healthy and unhealthy ash trees. Now we are studying and mapping genes within the tree that may be able to give resistance to ash dieback. We are also looking at the genome of the fungus itself and exploring the possibility of a breeding scheme to help secure a future for ash.

The Wakehurst tree team on the case

This is the first time we have had to close such a considerable stretch of the gardens, and for our Arboretum team, it’s no simple task.

The team, led by Arboretum Manager Russell, have been carrying out surveys across the site over the past few years, revealing that over 90% of ash trees at Wakehurst had signs of ash dieback.

They started by identifying infected trees to be removed around the site and began felling with the help of some heavy machinery.

“We have already made strong progress removing infected ash trees from roadsides around Wakehurst, as well as other areas within the gardens. The safety of our visitors and staff is our priority, so it’s essential we reduce and prevent the signs of ash dieback in our woodlands. Due to the instability of the trees, this is dangerous but extremely vital work.” - Russell Croft, Arboretum Manager

We look forward to welcoming visitors back into the Loder Valley as soon as it is safe to do so, and in the meantime the rest of Wakehurst’s biodiverse site remains open for exploration. From far-reaching meadows to sheltered woodlands, there are so many different habitats to discover.