11 November 2020

Taboo trysts between tropical trees: How hybridisation influences the Amazonian flora

By looking back across the landscape of evolutionary time, we’ve found another piece of the puzzle in the evolution of Amazonian tree diversity

The Amazon is the most biodiverse rainforest on Earth. How it evolved to be so diverse has fascinated scientists for years.

Many drivers have shaped its diversity, including major geographical changes such as the rising of mountains and shifts in river systems.

A powerful force

One factor that has been understudied, however, is hybridisation, where two different species reproduce and have offspring.

In plants, hybridisation is recognised as a powerful creative force in evolution, driving some of the variety we see in species through it’s effect on genetics and resulting physical characteristics.

It is much more common in plants than we think and, with at least 6,800 tree species in the Amazon, many of which are closely related, it’s hugely surprising that hybridisation has been overlooked as an aspect of the rainforest’s evolution.

In fact, for decades, scientists assumed that the process was essentially non-existent in Amazonian tree species.

Brilliant Brownea

Brownea is a genus of shrubs and trees in the legume family (that is, the same family as peas and beans). Native to tropical South America, Brownea species are a characteristic element of the Amazon rainforest.

Several species are cultivated in the tropics for their beauty. At Kew, we have B. grandiceps growing in the Princess of Wales conservatory and B. coccinea growing in the Palm House.

Many Brownea hybrids are also cultivated, such as B. hybrida and B. x crawfordii, both of which bloom with bright red flowers, but there are also possible examples of hybridisation occurring in the wild, they’ve just never been verified genetically.

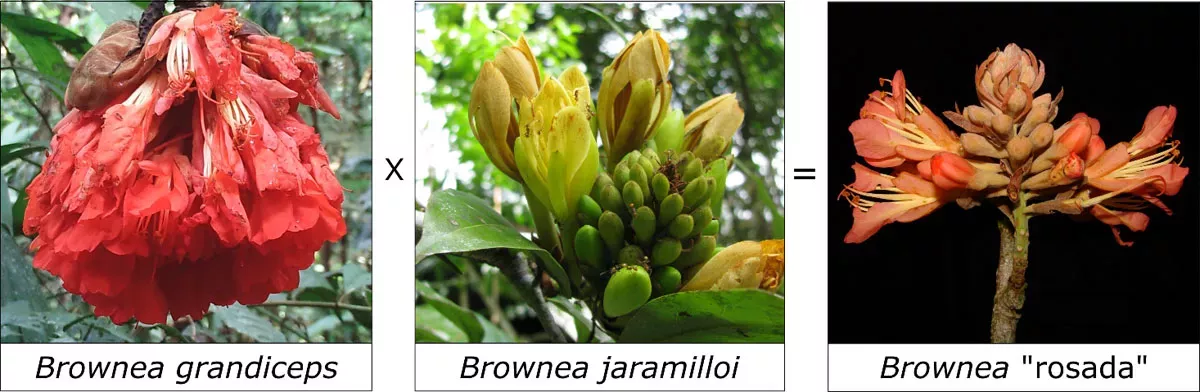

For example, B. jaramilloi and B. grandiceps both grow in the Ecuadorian Amazon and are very distinct from each other with different structures, flower colours, heights and even habitat preference.

Despite this, they seem to hybridise, producing a hybrid known as B. “rosada” which looks like a mix of its two parental species.

Ecuadorian adventure

We travelled to Yasuní National Park in Ecuador, where the Andes mountains meet the Amazon rainforest.

Mammals, amphibians, insects and plants flourish in the area, which boasts the highest biodiversity ever measured.

Using fresh plant material from two Brownea species that co-occur there, we were able to see from their DNA that hybridisation has recently occurred.

But what about in the past? To answer that question, we turned to Kew’s Herbarium.

We were able to get DNA from dozens of Brownea specimens in Kew’s Herbarium collection, some of which were ca. 150 years old, dating from William Hooker’s original Kew Herbarium.

Hybridisation over time

From the evolutionary trees that we built using the DNA data, we could visualise the patterns of hybridisation over time.

We found that hybridisation between species appears to have in fact been happening for millions of years.

Specifically, we discovered that closely related species occurring in the same area hybridise, which may help them to survive in very low-density populations spread over hundreds of thousands of hectares, as is typical of rainforest trees.

This may make them more robust to environmental change, since genes are being passed around between species, and the effective population size is larger than if mating was restricted to within their own species.

Tree diversity in the Amazon

Our work has given us a huge insight into how part of the Amazonian tree flora has diversified, and contrasts with previous theories about hybridisation within this incredibly rich flora.

Building up our understanding of how the Amazon evolved and diversified will help us to conserve its incredible biodiversity before we lose it.

Our future work aims to look at hybridisation and its effect on rapid ‘bursts’ of speciation (the evolution of new species) in the pea and bean family, to which Brownea belongs, and whose tree species dominate Amazonian forests.

Moreover, our genetics work will provide further insight into useful characteristics within the legume family, which is the second-most economically important plant family on the planet after the grasses.

Read the paper

Schley, R. J., Pennington, R. T., Pérez‐Escobar, O. A., Helmstetter, A. J., de la Estrella, M., Larridon, I., Sabino Kikuchi, I. A. B., Barraclough, T. G., Forest, F. & Klitgård, B. (2020) Introgression across evolutionary scales suggests reticulation contributes to Amazonian tree diversity. Molecular Ecology