12 August 2021

Unearthing alien species

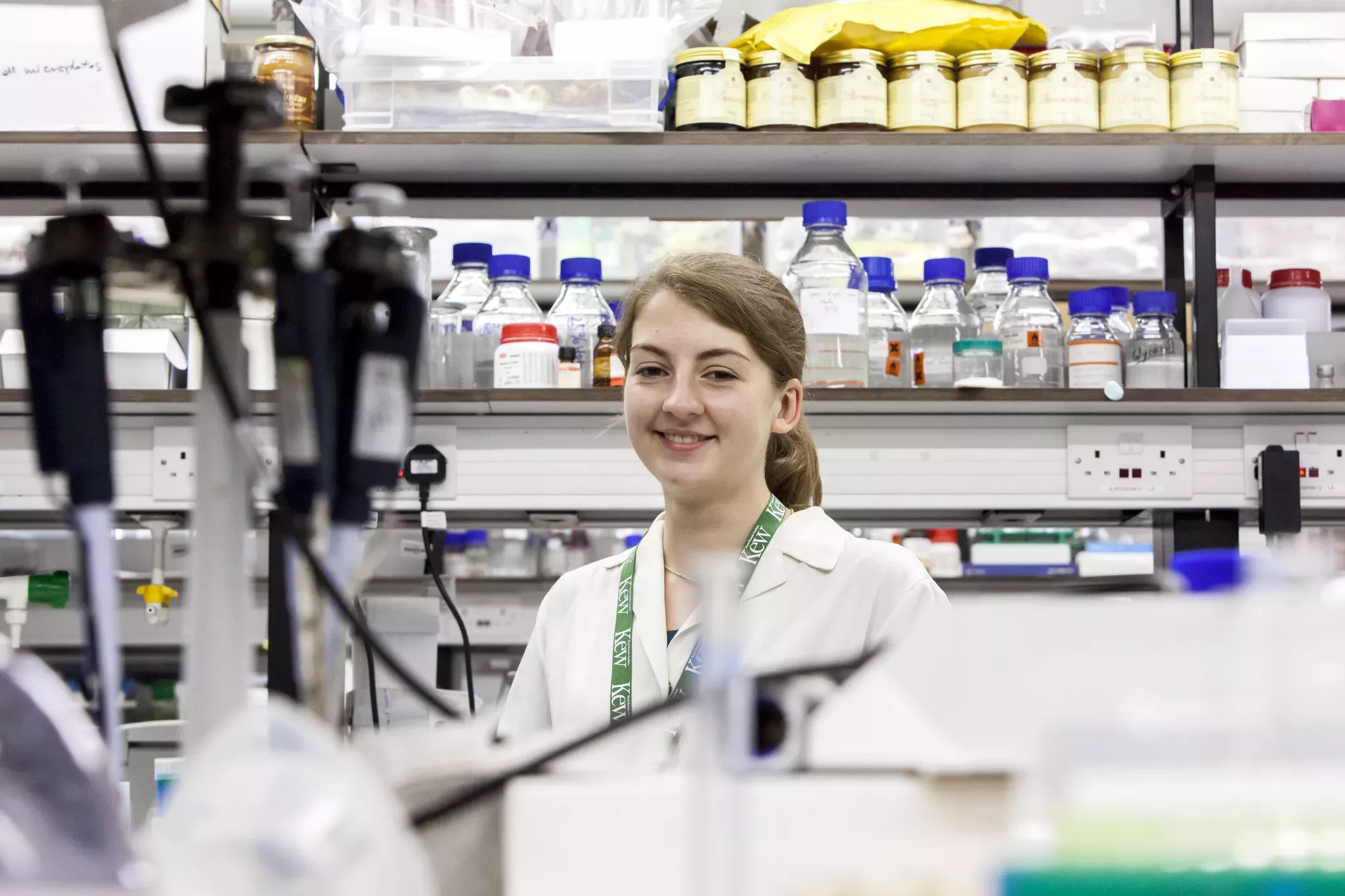

From the soil of South Georgia to the laboratories at Wakehurst, how is Kew identifying introduced plant species?

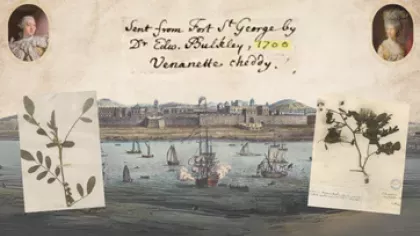

For hundreds of years, since the arrival of humans, the sub-Antarctic UK overseas territory of South Georgia has been plagued with introduced species.

These invasive non-native (or ‘alien’) species are a major driver of biodiversity loss, so controlling them is a high priority.

In 2016, following the successful removal of introduced mammals, an extensive non-native plant species eradication programme began to fully restore South Georgia’s natural habitats.

Penguin paradise

South Georgia is famous for its marine wildlife.

Penguins, seals and birds thrive on the uninhabited island.

Humans first arrived in the 1700s and the island later became a base for whaling in the 1900s.

With them came reindeer, rats and plants, which put pressure on the native plants and wildlife.

After the removal of the reindeer and rats, with the grazing pressure released, non-native plants flourished.

The island is home to 41 non-native plant species, outnumbering the 25 native species.

Kew scientists are supporting South Georgia’s efforts in eliminating non-native plants.

Five years on from the start of the eradication programme, have we seen success?

Soil, seeds and spades

The answer lies in the soil.

Searching for visible plants during summer is the easiest way to find non-native plants, but even if they have been killed off by herbicide above-ground, they may persist in the soil seed bank (the natural storage of seeds in the soil) and in the future could germinate to produce seedlings and new plants.

Back in 2017-2018, a team of scientists dug up soil samples across South Georgia to build a picture of which seeds are stored in the soil and how they are distributed over the island.

Following collection, the soil samples were sent to Kew’s seed laboratories at Wakehurst.

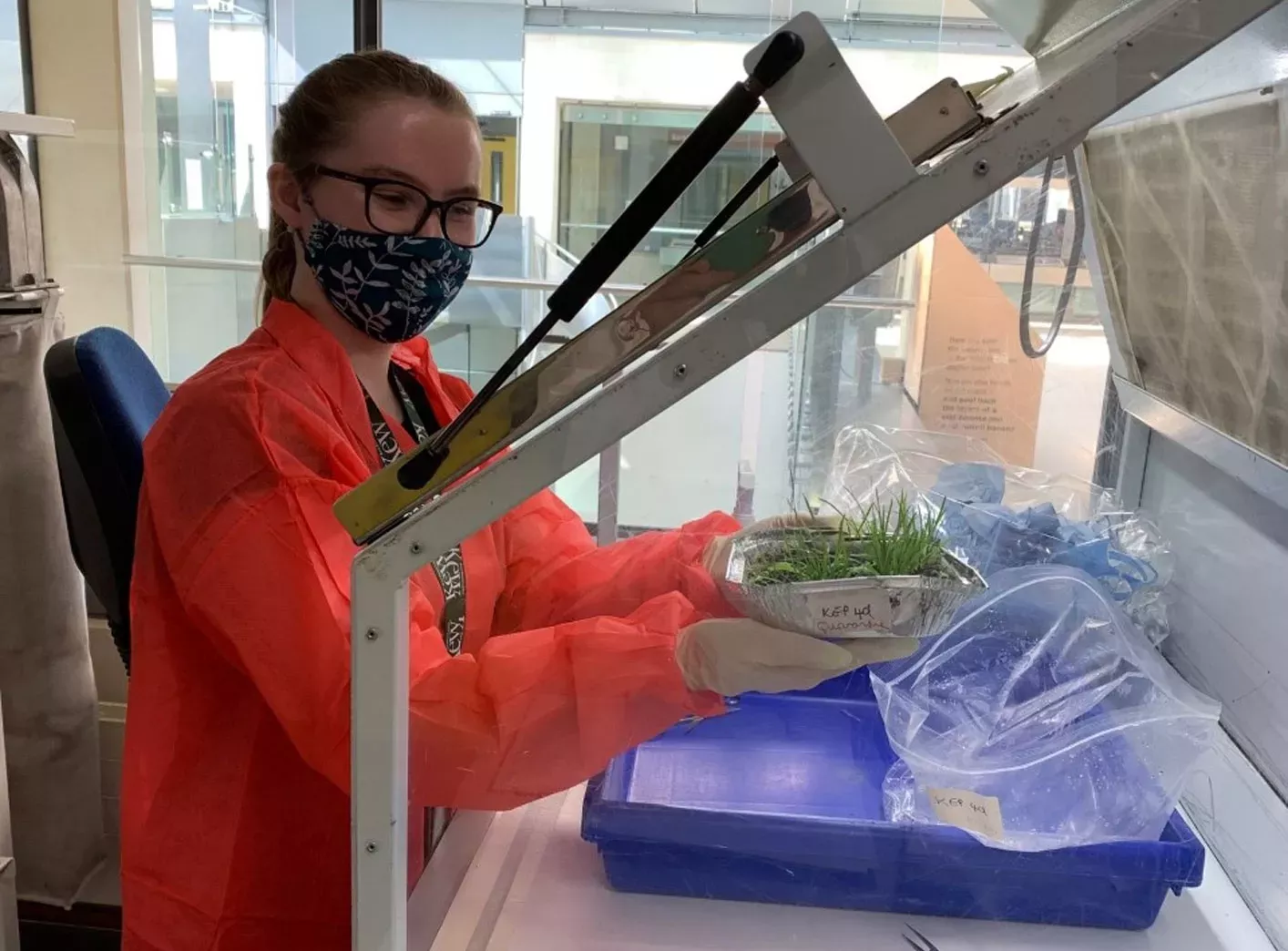

Quarantine at Wakehurst

Open the doors of a growth chamber at Wakehurst and you will find trays and trays filled with soil from South Georgia, many of them teeming with seedlings.

Every step involving this soil is carried out under strict quarantine conditions to protect the UK from potential invasive species that may be present, such as fungi, insects and plants.

Before entering the designated lab for the soil work, you must don a bright red disposable lab coat, overshoes and gloves, with a biohazard bag at the ready.

In a bay cordoned off from the rest of the room, with signs marking it as a quarantine zone, the bags containing the soil trays can safely be opened.

Once seedlings are big enough, they are harvested, dried, and sent to Kew for identification using molecular techniques.

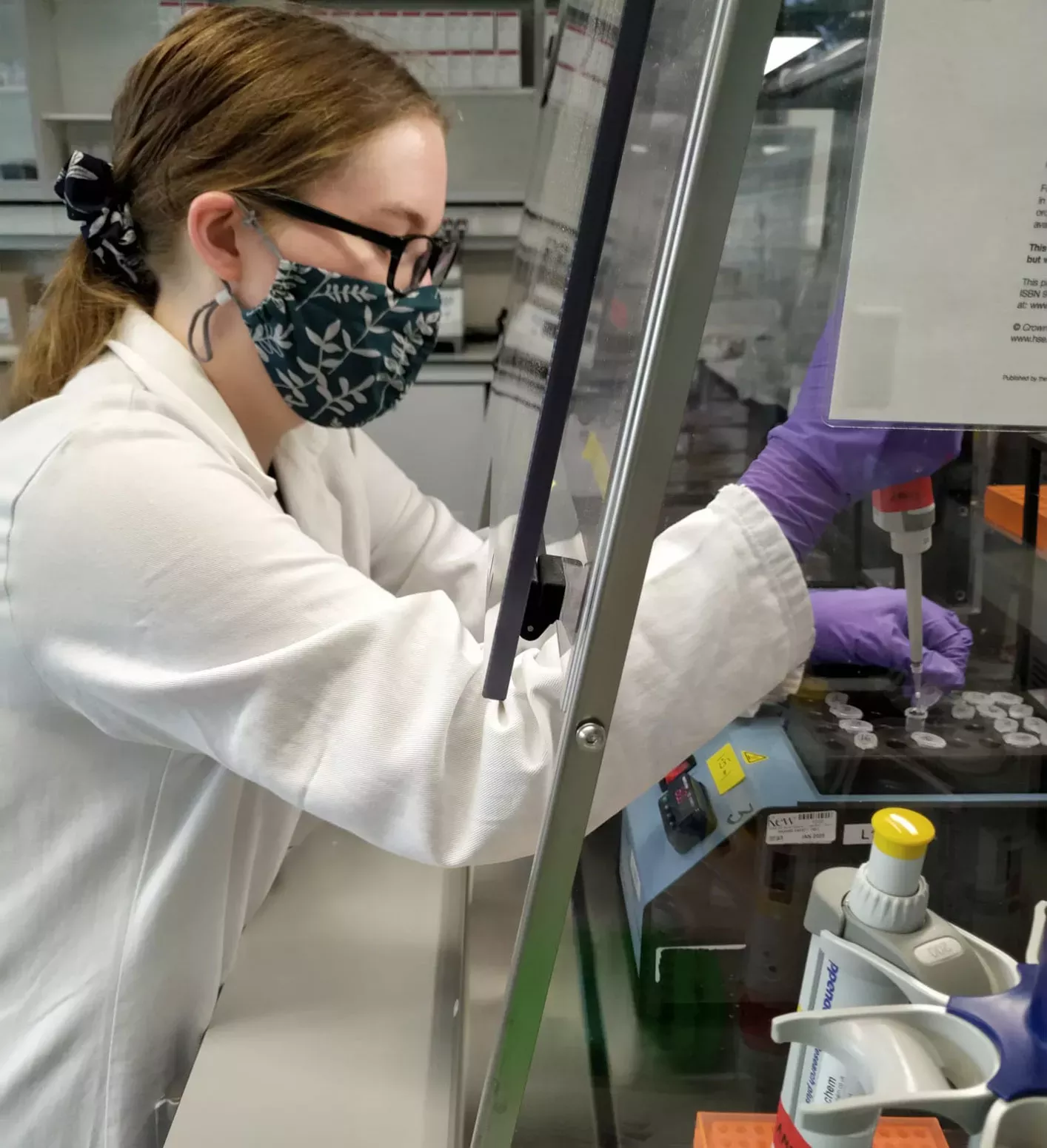

It’s in their DNA

As seedlings lack distinct morphological characteristics normally used to distinguish between species, we are looking at differences in their DNA sequences to identify species, a method defined as DNA barcoding.

Several steps are needed to extract DNA and prepare samples for sequencing, a process that takes 4-5 days to complete.

As an intern, my job has been to help with preparing these sample so that they are ready to be sequenced.

We are currently sequencing the DNA of all known native and non-native plant species found on South Georgia and will create a phylogenetic tree with these data.

It’s like building a family tree for the plants of South Georgia.

Thereafter, we will incorporate the unknown and unidentified samples, that were dug up, into the tree, enabling us to identify which species they are and whether they need to be eradicated

We are hopeful that after five years of control, none of the introduced species will be found in the soil seed bank.

Although, we do expect to see some groups of non-native species that are too widespread to be eradicated to be present in the soil seed bank, along with seeds of native plant species.

If seeds of any of the introduced species are found in the soil, further control will be needed.

The future of plant management on South Georgia rests on the successful identification of plant species from our sequence data.

Only then will we finally have an answer to which introduced species are still present on the island.

It has been an exciting project to be a part of, contributing to work that will have a real conservation impact.

Acknowledgements

Indigena Biosecurity International

Government of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

Thanks to funding from the Darwin Initiative