9 May 2019

How Kew’s wood experts solve crimes

Wood anatomist Dr Peter Gasson reveals how we help fight the illegal timber trade and aid police investigations.

Thwarting illegal timber trades, solving murders and identifying poisons are just some of the ways Kew’s wood and timber scientists help combat crime.

Dr Peter Gasson, our lead and often sole wood anatomist, regularly receives wood and timber material to identify from a range of different organisations and individuals, including customs and police, archaeologists, palaeontologists and antique dealers.

Our wood collection

Helping solve certain crimes wouldn’t be possible without our microscope slide reference collection.

We have one of the biggest general microscope slide reference collections in the world as it includes monocots, dicots and conifers, with around 100,000 microscope slides.

Stored in fireproof cabinets within Kew’s Jodrell Laboratory, this extensive collection has been built up since the 1930s and contains samples taken from leaves, stems, twigs and woods.

We also have nearly 50,000 wood samples, as seen in the image below.

Wood identification

‘Aside from producing books on the anatomy of dicots and monocots, we use our reference collection and expertise to identify fragmentary plant material,’ Peter says. ‘That could be anything from a piece of wood to a twig to a concoction of leaves to a traditional Chinese medicine to gut contents from an animal or person who has been poisoned.

‘Most of my work is on timber, identifying woods in furniture or plywood. The questions to be answered are 'what is it?' and 'where does it come from?’'.

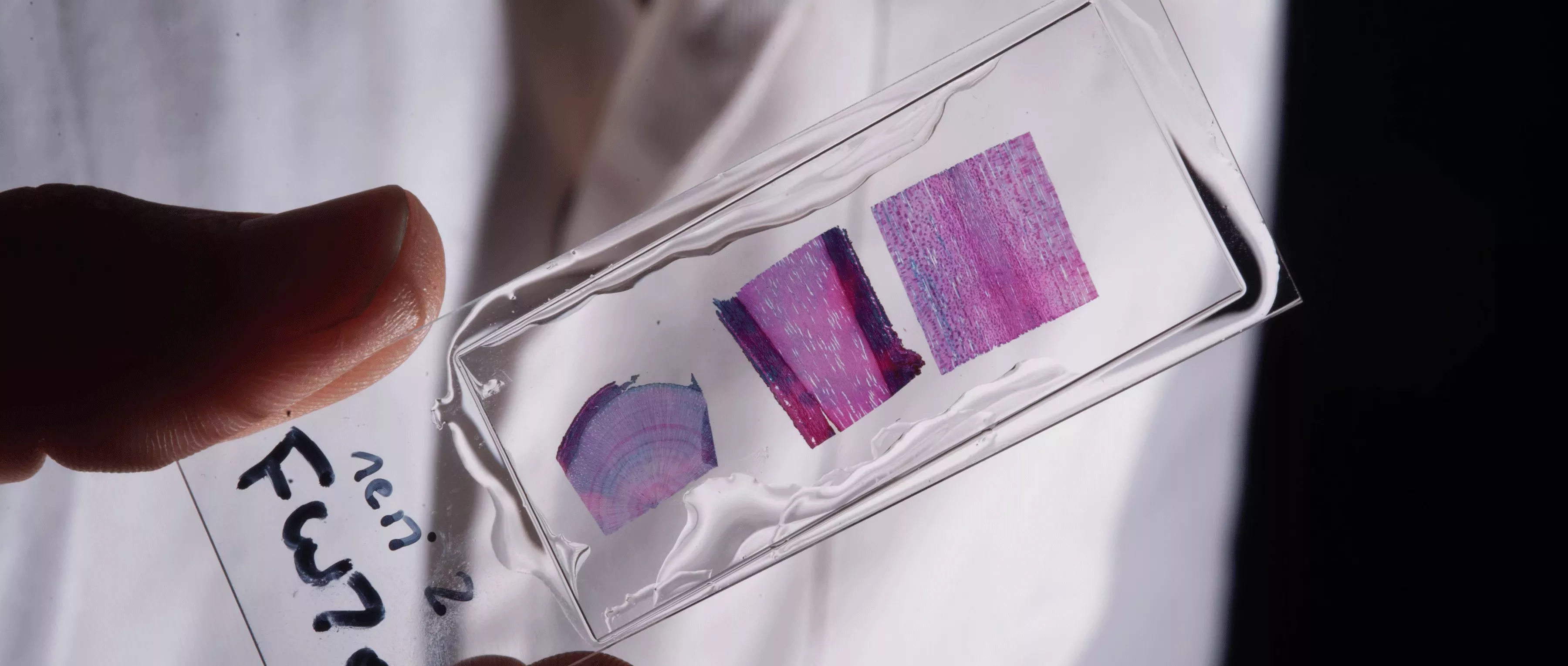

The naked eye can be enough for our wood experts to tell the difference between a softwood and a hardwood. But for more specific identification microscopy is needed.

In this case, a sample of the wood is softened by boiling it in water. Some heavier woods such as ebony (Diospyros) may also require microwaving or chemical treatment.

Once softened, sections are cut in three planes, transverse (TS), tangential longitudinal (TLS) and radial longitudinal (RLS), using a piece of equipment called a microtome and then examined under a light microscope.

Illegal timber trade

Wood identification plays a key role in uncovering illegal timber trade.

‘UK Border Force are generally only interested in things that are CITES-listed (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species),’ Peter says. ‘If you don’t have the correct import and export permits for CITES timber then it’s illegal.’

As the official CITES Scientific Authority for Flora in the UK and part of the Global Timber Tracking Network, Kew uses its unique wood archive to identify timber being illegally smuggled.

If Border Force suspect that a wooden item is CITES-listed they can send it to Kew for authentication to either confirm or refute what they think it is.

Suspect items have included guitars with fingerboards thought to be made from CITES-listed rosewood (Dalbergia) and blinds made from endangered ramin (Gonystylus).

‘Quite often with furniture what you see on the outside is not what’s inside,’ Peter says. ‘Some pieces can be made from many different woods.’

All parts of the sample need to be tested to make sure they are all the same. It’s more complex if Border Force want to know exactly what a sample is and will require more analysis.

Finding the wood's origin

Timber is sometimes exported from the country where it grew to the country where it was turned into a product and then exported again. So it’s difficult to know the location of origin. A product can be made from wood from many different continents.

‘One technique called stable isotope analysis can tell you where the tree came from,’ Peter says. ‘For example, to find out if a Palaquium wood sample is from the Solomon Islands or Papua New Guinea, the stable isotope pattern from those two places will be different. So if you’ve got reference material from both places, you’ll be able to match it up.

‘Before you can produce any reference databases on stable isotopes or anatomy or molecular stuff, you need the material. We are trying to build that up.’

Helping solve murders

The most graphic case the department has dealt with is the police investigation of 'Adam' in the River Thames. The torso of a five-year-old west African boy with no head, arms or legs was discovered at Tower Bridge in 2001.

Our experts aided the investigation by analysing the gut contents of the dismembered body and identifying nearly every item in there, including Physostigma venenosum, the calabar bean, which is highly poisonous.

This forensic information helped the police work out the murder was likely a ritual sacrifice. But sadly, they have never found out the boy’s true identity or who committed the crime.

Mummy coffin discoveries

Some of the requests the department receives are archaeological in nature.

‘I was sent a couple of tiny scraps of wood that came from the inside of a mummy coffin,’ Peter reveals. ‘Under the microscope, I could see scalloped tori in the bordered pits which are distinctive characteristics unique to the genus Cedrus.

‘I compared this to a cedar slide from our reference collection. We can put two slides on the microscope at once, comparing the reference and enquiry slide to one another. Egyptian conifer wood is often Cedrus.

‘Sometimes you can tell what the whole tree was just from a tiny scrap which I think is pretty amazing.’

Top challenges

The biggest challenges are the two questions; what is it and where does it come from?

Identification can be difficult. In some families the genera are so similar or there isn’t enough knowledge to determine what it is.

‘Ideally, we can identify things to genus level but sometimes we can’t,’ Peter says. ‘And sometimes, even when we get to the genus, there are 100 or 200 species in that genus.

'Different species within a genus can be difficult to tell apart especially when you don’t know what the provenance is. Often the legislation is a bit beyond the science to actually deal with it.’

Building an extensive and deep reference collection is essential. For example, there are 530 species of oak but currently we only have specimens of a quarter of that.

‘The aim is to build up as good a reference collection as possible, being able to pinpoint where things come from,’ Peter says. ‘Then we can build up both reference wood sample sets and also databases with various techniques from them.

'Without that you can’t answer those two key questions – what is it and where is it from? It’s a bit ambitious but you’ve got to start somewhere.’