26 July 2019

Nature's true colours

Colour is everywhere. But how do things become coloured, how is colour used and determined, and why does it matter?

Why is colour important to science?

The natural world is full of bold, beautiful, diverse colours.

Botanists and mycologists need standardised colour terms for the precise identification of plants and fungi when working both in the field and with dried, pressed specimens.

In both cases, it is important to keep a record of colour that will outlast the colour of the specimen itself, which by nature is short-lived. Once a plant is dead, it starts to lose its colour, for example.

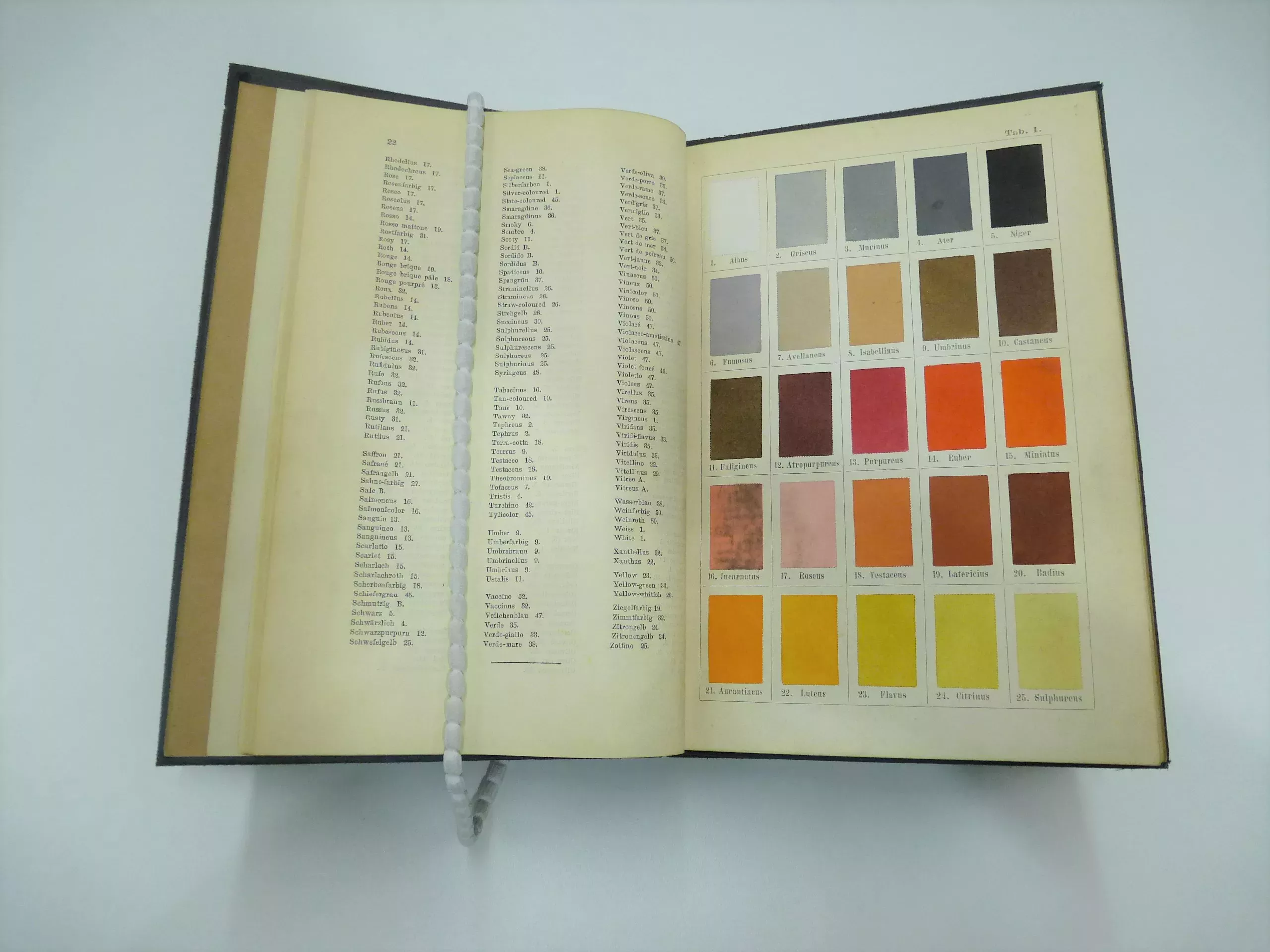

Colour charts and naming systems were created to assist with this task and help to illustrate the important connections between art and science.

However, this is not as simple as it might seem. Pier Andrea Saccardo, an Italian botanist and mycologist, produced the first colour naming system in 1891 specifically for use by mycologists: Chromotaxia

Saccardo’s colour names were widely used, but subtle differences between colours in different printings of Chromotaxia and the effects of ageing of the print itself, have caused confusion over the appearance of the original colours. This is a very important issue when colour is to be used as part of scientific data.

Colours through the ages

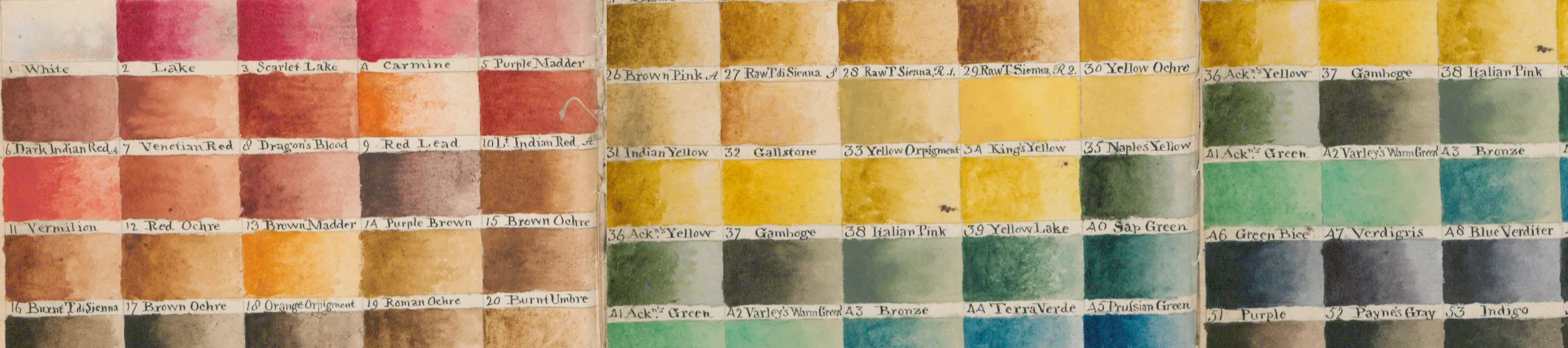

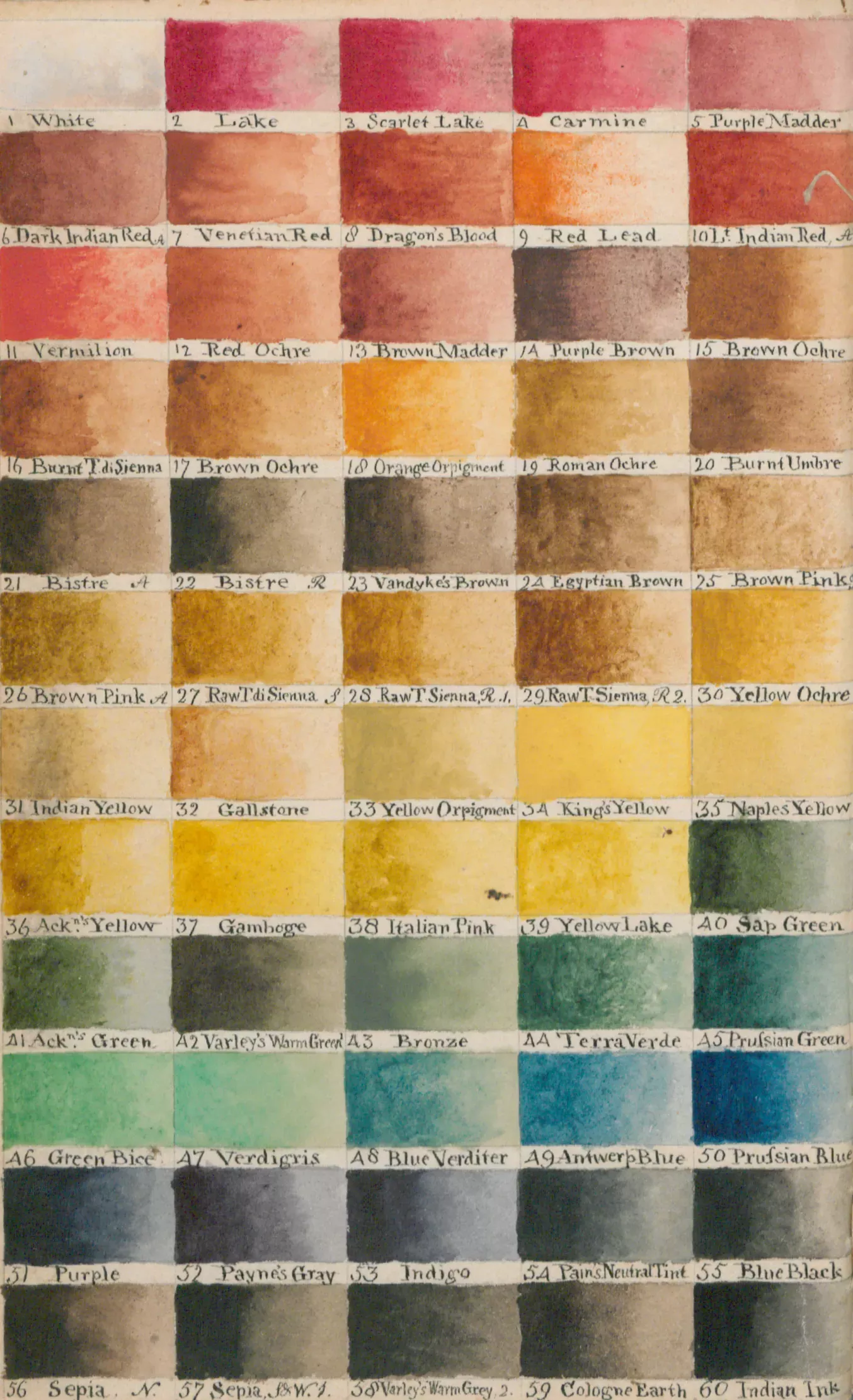

William Burchell (1781-1863) painted colour charts between 1825-1830 to aid identification of the plants he was collecting whilst travelling in Brazil.

The charts show 60 colours ranging from white to Indian ink, along with assigned names and numbers to assist in describing the appearance of the plants.

Burchell included colour names like Gallstone (yellow), Antwerp (blue), and Italian Pink (which is, surprisingly, yellow).

A second, similar colour chart has sections of Burchell’s travel itinerary written alongside it. Having these colour references to hand whilst travelling would have been invaluable to him. Over the last three decades of his life, he extensively catalogued the specimens he collected, and used these colour charts to add detail and maintain accuracy within his work.

His material from Brazil, totalling more than 52,000 specimens, was only catalogued in 1860. These catalogues are regarded by naturalists as basic sources of exceptional historical value on the botany of St Helena, South Africa and Brazil. After his death in 1863, Burchell’s sister Anna donated Burchell's collections and manuscripts to Kew.

The story of indigo

One of the oldest and most valued dyes in the world, indigo has been used for millennia in many different parts of the globe.

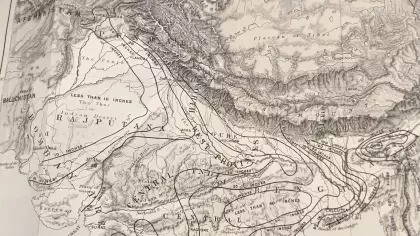

While many plants are sources of the indigo dye, it is mostly obtained from those of the genus Indigofera.

Indigo-bearing plants are widespread. They produce a dyestuff that is very colourfast, and, unlike other natural dyes, is compatible with animal and vegetable fibres. Indigo dye can also be used to create a whole range of colours difficult to reproduce naturally, like purples, blacks, and greens.

With a long history of economic and cultural importance, as well as links with Kew and the British Empire, indigo has an extensive history.

The Economic Botany Collection has a wealth of indigo-related material including this indigo printing block.

The mystery of Indian Yellow

The origin of the Indian Yellow pigment has long been disputed.

In 1883 Trailokyanath Mukhopadhyay, the curator of the Indian Museum in Calcutta, was asked by Kew director Sir Joseph Hooker to investigate a possible animal source of the dye.

Mukhopadhyay reported that he traced the pigment to a town called Monghyr, and that it was produced from the urine of cows that were fed exclusively with mango leaves!

Supposedly, this discovery ultimately led to the making of Indian Yellow being forbidden on grounds of cruelty to the cows. However, no record of this, nor indeed of the unusual making process, has ever been found, and some even suspect the story of the cows to have been a joke played on the British by Mukhopadhyay.