24 June 2019

Saving rosewoods, one datapoint at a time

In the battle against illicit trading in endangered tropical rosewood, Kew’s historic Herbarium is providing conservationists with a vital new weapon: data.

What is the most widely traded illegal wildlife product in the world? The answer is not ivory or rhinoceros horn – but rosewood.

The fragrant tropical hardwood is prized especially for making furniture, although it is also a favourite material for guitars, billiard cues and chess sets.

Today, the global rosewood trade is worth significantly more than elephant ivory, rhinoceros horn, pangolin scales, big cat skins and tortoise shells combined.

The illegal trade is being driven by demand in China, where ornately carved pieces are status symbols for the nouveau riche and a large rosewood bed can sell for $1 million.

Tropical forest crisis

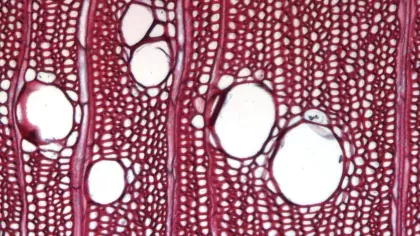

The modern world’s soaring appetite for rosewood furniture has triggered a crisis in tropical forests. Their serial depletion poses a substantial risk to the survival of some species of the rosewood genera Dalbergia and Pterocarpus.

Illegal logging occurs around the world, but the trade is especially damaging in Madagascar where the loss of mature trees is destroying unique forests ecosystems and threatening the habitat of the island’s famous lemurs.

Action is finally being taken. Two years ago, all Dalbergia and two of the timber species of Pterocarpus were listed under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), slapping a ban on their trade. But loopholes in legislation, corruption and limited enforcement mean illegal logging still continues, leaving scientists and conservationists grappling to establish the facts.

Data to the rescue

Now they have a new tool to help map the exact status of key rosewood species and the scale of the threat they face, thanks to a data mining project using Kew's Herbarium, one of the largest treasure troves of botanical specimens in the world.

The Herbarium, built in 1877, contains in excess of 7 million plant specimens dating back more than two centuries and is still being added to every day.

Together with smaller collections at London’s Natural History Museum and the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, it holds around 85% of all known plant species – including thousands of rosewood records.

For the first time, the three British scientific centres have joined forces in a mass digitisation programme that will put key information online, allowing researchers to access taxonomic, habitat and geographical data that would otherwise be unavailable unless scientists physically visited each institution.

Under the project, funded by the British government’s overseas aid budget, a total of 37,000 legume specimens have now been digitised.

Kew staff and volunteers contributed nearly two-thirds of the total. The programme includes not only rosewoods but also dry beans from the subtribe Phaseolinae, which are important for food security in many countries, yet are in decline in certain parts of the world.

The detailed information and high-resolution images will enable scientists at Kew and international research institutions to refine the geographic ranges of plants and help conservationists undertaking extinction risk assessments for rosewoods by highlighting the distribution of different species.

Altogether there are around 250 separate species of Dalbergia and 40 of Pterocarpus, many endemic to particular regions of the tropics. The natural history of most of these species remains poorly understood.

The Herbarium’s deep historical records mean it can also shed light on how the spread of species has changed over time. Effectively, scientists can travel back in time to see how plants were distributed in the past, letting them reconstruct the extent of forests that may have since been destroyed by human action or climate change.

In some cases, tapping this history involves a degree of detective work, including retracing of itineraries of famous plant-collecting expeditions – such as the Expedition to the Sources of the Nile in the 1860s – in order to work out exactly where certain species were growing at the time.

Hopefully, the benefits will not stop at rosewoods and dry beans. The team at Kew believes the high-throughput methodologies used to digitise these specimens will also act as a pilot study for a host of future collaborative mass digitisation efforts in other areas of botany.