22 April 2022

Plants in Shakespeare

On the 406th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death, we take a look at the influence of flowers and gardening on his works.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) grew up in Stratford-upon-Avon. His plays reflect his great affinity for flowers and gardening which has been partly attributed to this country-dwelling upbringing.

There was also much innovation in gardening and botany in Elizabethan London, plus Shakespeare was a regular visitor to formal gardens.

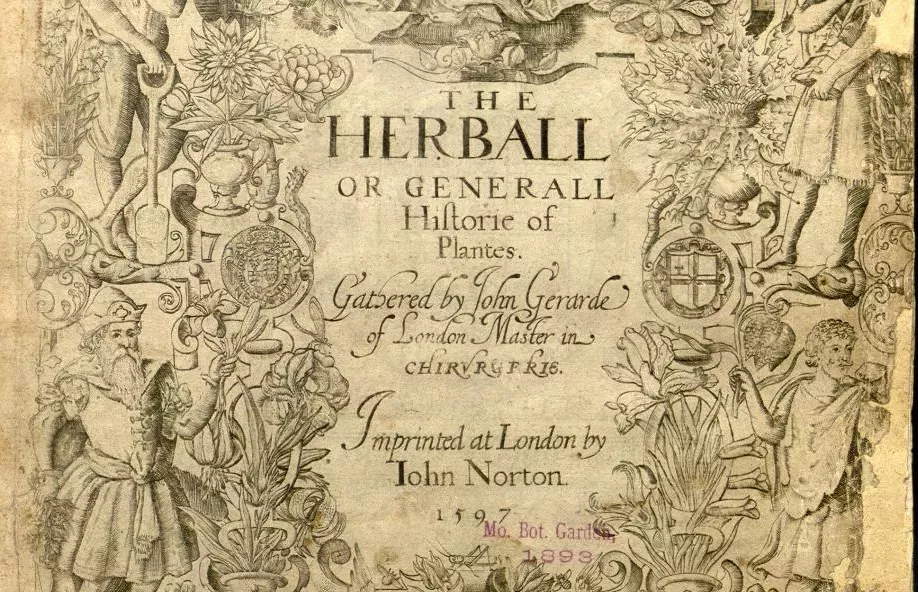

He also would have been familiar English herbalists and botanists such as John Parkinson and John Gerard.

Elizabethan gardens

Identifying plants in Shakespeare's works can sometimes be difficult, but the types of Elizabethan garden that Shakespeare alludes to are well-documented in plans of the time.

Elizabethan gardens included fruits, vegetables, and healing herbs, but they were also for pleasure. Many features were designed purely for decoration, or for social purposes such as the arbour, an archway formed by plants.

The knot garden, a garden design of geometric shapes using small aromatic hedges, had been a distinct feature since Tudor times, being modelled on those popular in France and Italy.

Sweet-smelling herbs

Elizabethan gardening was a well-developed art. The planting of flower gardens was structured to ensure they were always in bloom, with the colours and perfumes complementing each other.

Scent was given as much emphasis as the appearance of flowers. There was more appreciation than there is today of sweet-smelling herbs such as camomile being part of the aesthetic delights of a garden, although their culinary and medicinal uses were recognised as well.

Oberon: I know a bank where the wild thyme blows,

Where oxlips and the nodding violet grows,

Quite over-canopied with luscious woodbine,

With sweet musk-roses and with eglantine:

There sleeps Titania sometime of the night

[A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act 2, Scene 1]

A rose by any other name

Roses are referred to around a hundred times by Shakespeare, probably influenced to some extent by their link to the Tudor dynasty as well as the flower’s own obvious merits.

Often the reference is to ‘briar’ or, as in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, to ‘eglantine’ (now identified as ‘sweet briar’).

Woodbine and honeysuckle

‘Woodbine’ is a name still used today, but now to describe very different climbing plants and creepers.

It is thought to be ‘honeysuckle’ based on Shakespeare’s descriptions and herbals (books describing the various properties of plants) at the time. Later in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Titania says 'so doth the woodbine, sweet honeysuckle entwist'. This seems to be describing honeysuckle as the flowers of the woodbine plant.

The audience would have known that, like many herbs, thyme releases its scent when blown by the wind or if crushed (as here with Titania sleeping on it). Thus it makes sense that it is included in the description of a highly perfumed arbour-like area of a wood.

Leather-coats and crabs

Shallow (to Falstaff): Nay you shall see mine orchard, where, in an arbour, we will eat a last year’s pippin of my own graffing, with a dish of caraways, and so forth. [….]

Davey: There’s a dish of leather-coats for you

[Henry IV, Part 2, Act V, Scene 3]

‘Pippin’ continues to be a popular apple today, and ‘leather-coats’ refers to a type of russet that was popular at the time. ‘Caraways’ refers to a popular dish of apples flavoured with caraway seeds.

As well as those mentioned, 'crabs' (as in crabapple) are referred to in many of Shakespeare's plays. They were popular to eat in Elizabethan times although today thought too bitter and now only generally eaten as a jelly.

The orchard and arbour were important features of the Elizabethan garden.

The use of ‘graffing' (grafting) shows Shakespeare’s gardening knowledge, and the concept is used in other plays along with references to pruning such as 'thy pole-clipt vineyard' in The Tempest.

Queen's Garden at Kew

The Queen’s Garden outside Kew Palace only features plants that were known or became known during the 17th century. It is therefore a good place to imagine the garden setting of Shakespeare’s plays, and the plants referred to within them.

Further reading

All the titles below are available to view at Kew's library:

Ellacome, Rev. Henry N. (1878).The Plant-lore and Garden-craft of Shakespeare.

Gerard, John (1597). The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes.

Guilfoyle, W.R. (1899-1901). Shakespearean Botany Nos.1-24.

Halliwell, Brian (1987). Old Garden Flowers. Bishopsgate Press.

Rydén, Mats (1978). Shakespearean Plant Names. Almqvist & Wiksell.

Parkinson, John (1629). Paradisi in sole paradisus terrestris.

Seager, H.W. (1896). Natural History in Shakespeare’s Time. Elliot Stock.

Singleton, Esther (1923). The Shakespeare Garden. The Century Co.