22 December 2013

The taxonomy & evolution of Christmas trees and their relatives

Rhian Smith takes a closer look at Christmas trees and their relatives, and describes the scientific work Kew is carrying out on the taxonomy, biogeography and evolution of this important group of plants.

Every December, families across the world bring conifers into their home and the Christmas tree becomes the centrepiece of the festive period. But how many realise that their tree is part of a plant lineage stretching back over 300 million years, spanning continents and climate zones?

Conifers are often indiscriminately referred to as ‘fir trees’ and yet the genus Abies (the true fir) contains only 47 of the 615 species of conifers worldwide. Those used as Christmas trees span at least three genera, and the various species include Norway spruce (Picea abies), blue spruce, (Picea pungens), white spruce (Picea glauca), Nordmann fir, (Abies nordmanniana), Fraser fir (Abies fraseri), white/Weymouth pine (Pinus strobus), Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), and lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta).

To challenge perceptions of conifers further, Podocarpaceae (the second largest of the eight conifer families after Pinaceae), is largely a tropical family of island species, with its main centre of diversity in the Southern Hemisphere. This takes us a long way from the snowy forests of Northern Europe, and a groundbreaking new scientific publication from Kew and the University of Oxford throws up even more facts and surprises about the distribution, biogeography and conservation of this fascinating plant group.

A global atlas of conifers

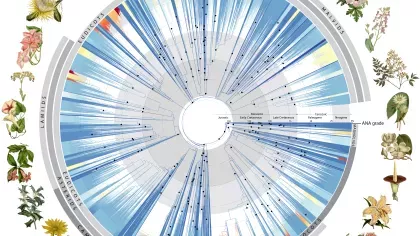

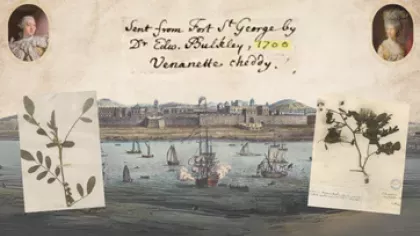

An Atlas of the World’s Conifers by Kew’s Aljos Farjon, the world’s foremost expert on conifer systematics, and Denis Filer, an expert in plant diversity and botanical database management from the University of Oxford, is the first ever atlas of all known conifer species. Based on 37,000 specimens from 337 herbaria, this remarkable piece of work contains descriptions and maps of the global distribution of each of the 615 known species of conifer, and builds on Farjon’s earlier taxonomic works, World Checklist and Bibliography of Conifers and A Handbook of the World’s Conifers. It also includes the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List categories for species under threat.

A unique feature of the Atlas of the World’s Conifers is that the entire dataset is available online and each distribution point can be queried, linking back to the details of the original herbarium specimen collection. This means that each point is independently verifiable and it is an incredibly useful resource for further research into conifer systematics, biogeography, evolution and conservation.

This work has already highlighted important biogeographic trends in global distributions and hotspots of biodiversity. One striking pattern that has been identified is a substantial gap in conifer occurrence in the Andes between the latitudes of 30 and 33 degrees south. This absence of conifers coincides with a region known as the South American Arid Diagonal (SAAD) and the authors suggest that insufficient precipitation is a major contributing factor to this pattern, along with an absence of taxa that could adapt to these conditions when they developed 14–15 million years ago (Ma).

In addition to insights such as this, the data provide the foundation for further research into biogeography, systematics and conservation, and have already been used for calculating species distribution models. These models, which use the present day distribution of the species alongside the climate variables apparent in this area to create a ‘climate envelope’, are important tools to model the future distribution of species under predicted climate changes. Given that over a third of conifers are currently under threat, understanding the impacts of climate change on the distribution of these threatened species is an important conservation goal. When combined with phylogenetic information, such data can also underlie powerful analyses of patterns of speciation and dispersal.

More distant relatives

Conifers, along with the cycads, Gnetophytes (Gnetum, Ephedra and Welwitschia), and Ginkgo, are part of a group of plants known as gymnosperms (literally meaning ‘naked seed’, as opposed to the flowering plants or angiosperms, in which the seeds are enclosed). The modern-day distribution of this group reflects both the break-up of the ancient supercontinent of Gondwana through continental drift, and more recent long distance dispersal events, making it a fascinating and rewarding target group for increasing scientific understanding of the processes that shape plant diversity, distribution, ecology and evolution.

This group also contains unique genetic lineages, such as the very distinct Welwitschia (pictured below), and Kew is leading the way on a project to characterise this evolutionary novelty and combine it with data on rarity to prioritise species for conservation.

Researchers at Kew are currently reconstructing a phylogenetic tree comprising about 80% of all described species of gymnosperms using DNA sequences. Soon, we will know which gymnosperms are the most evolutionary distinct and globally threatened. I don’t think any of the humble Christmas tree species will make the list, but watch this space…

References

- Farjon, A. (2001). World Checklist and Bibliography of Conifers. Second Edition. Kew Publishing, Kew, Richmond.

- Farjon, A. (2010). A Handbook of the World’s Conifers. Vols 1 & 2. Brill, Leiden & Boston.

- Farjon, A. & Filer, D. (2013). An Atlas of the World’s Conifers. An Analysis of their Distribution, Biogeography, Diversity and Conservation Status. Brill, Leiden & Boston.

Related links

An Atlas of the World’s Conifers