Splitters and Lumpers

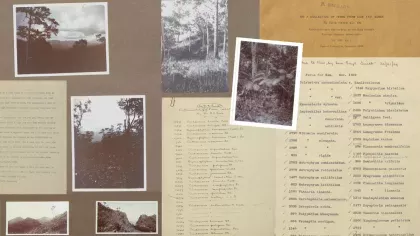

In a guest post, photographer Liz Orton discusses how her photo series Splitters and Lumpers was inspired by Kew's Herbarium. Her images are on permanent display in the Herbarium.

I’ve had a remote relationship with Kew Gardens for a number of years through my partner who worked there. One day he came home with video footage of then-director, Professor Stephen Hopper, opening and closing cupboards in Kew's Herbarium to show specimen after specimen of dried plants, including now extinct species.

This appeared to me an act of wonder: a seemingly ordinary cupboard yielding such extraordinary objects. The specimens, so delicate and still blushing with colour, yet with no living representatives in the world, seemed like treasures to me. I longed to wander the corridors and open some of those cupboards myself. Since I’m not a taxonomist or botanist I wondered if I might be able to do this in my capacity as a photographer.

I was introduced to botanist Gemma Bramley who showed me around the cupboards and patiently answered my questions about plants and classification. She showed me how to handle specimen folders, and herbarium sheets, and introduced me to the most basic elements of the classification system.

For my first few visits I spent quite a bit of time wandering amidst the shelves, climbing up and down stairs, enjoying the experience of feeling lost. Literally lost, as I kept getting disorientated and coming out in the wrong place, but also conceptually lost as I understood very little of the complexity of the Herbarium.

As I didn’t have enough botanical knowledge to navigate in any meaningful way, I experimented with random patterns and variations: opening cupboards vertically, diagonally, by number, by countries I’d visited or names I recognized.

I quickly realized that although great pleasure was to be had in looking at the mounted specimens, I had no urge to photograph them, and it seemed a little pointless as many specimens have already been scanned as part of ongoing digitization projects.

What interested me was the relationship between the systems of organization in the herbarium and the natural world.

When I start a new series of work, I have only a vague sense of the actual subject. I have to start making work to feel my way into what it might become. So I photographed a lot of cupboards to begin with, and quite a few bundles, as a way of thinking things through. I became very absorbed in reading histories of plant collecting, classification and naming.

One day when I arrived at the Herbarium, several trolley loads of boxes had been parked together to form a vast tower of green boxes. The reorganisation of material seemed to me an important subject – the idea of an old order straining under the weight of new knowledge, old categories falling apart, new categories forming. Would there ever be a time, I wondered, when knowledge was so complete that herbaria would no longer need to be reorganised?

I started paying more attention to piles of specimens that were waiting to be classified. Piled anonymously on desks, in cupboard and cabinets, they seemed unruly compared to the mounted specimens. They were the specimens that hadn’t yet been processed, many of them new acquisitions.

I developed a small passion for these bundles – collections of plant specimens packaged in whatever material came to hand – mostly newspaper. Unlike mounted specimens, these waiting piles seemed to exhibit no regular form or standard, each yielding its own stories and possibilities. I liked the fact that they were transitional, existing only temporarily.

I felt that these temporary bundles were interesting as objects and forms in their own right and that if I could decontextualise them, I could draw visual attention to them. Gemma kindly let me turn her desk into a temporary studio and I made the photographs by taking extracts from the piles and photographing them against a black backdrop which made them appear as if suspended or floating.

The sideways view of specimens in layers of paper creates a kind of stratigraphy of nature and culture. It focuses our eye on the surfaces and edges of the paper and the specimens. Attempts to see into the image, to penetrate the depths, are frustrated.

I made about 40 of these images over about six months. I could have carried on for much longer – every time I found a new bundle to photograph in the to and fro of the collection was an exciting moment. But working with film is time-consuming and expensive.

I wavered for a long time about whether to caption the images. I would have been happy not to. Personally I did not feel the need to put the taxonomical context back in but I felt it would be appreciated by those working in the herbarium, for whom the data is part of the specimen, not separate from it. So I decided to caption them using information I had copied from notes accompanying the dominant specimen(s) in each image.

I called the series Splitters and Lumpers fairly early on, before I’d finished photographing them. This phrase in taxonomy refers to the opposing tendencies of dividing or grouping organisms based on the differences or commonalities between them.

My experience of being in the Herbarium continues to influence my practice and I continue to make work exploring social ecologies in different ways.

- Liz -

Liz’s images can be seen at her website or by accredited researchers visiting Kew's Herbarium.