Plants: From Roots to Riches

Kew's Director of Science, Professor Kathy Willis, describes the BBC Radio 4 series Plants: From Roots to Riches. The series provides a unique examination of the major breakthroughs in botanical science, as seen through the lens of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Beginning on Monday 21 July, the BBC Radio 4 series Plants: Roots to Riches provides a unique examination of the emergence of the academic discipline of botany, a timeline in the development of the subject from its first beginnings through to the present day. It focuses on the major breakthroughs in botanical knowledge over the past 250 years and places them within their historical context as seen through the lens of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew.

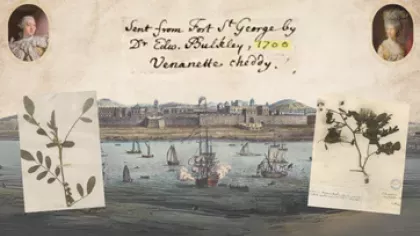

In some cases Kew was the institution leading the scientific breakthrough, in others it was responding to work elsewhere. Kew has always provided a central clearing-house for both ideas and specimens from all corners of the natural and the intellectual world. This series maps the journey with interviews, discussions and examples of past and present work at Kew. The series involves contributions from a large number of Kew scientists, horticulturalists, volunteers and guides alongside contributions from historians and plant scientists from other institutions.

The timeline for this series starts in 1753 with the development of Carl Linnaeus’ binomial classification system for plants (and animals). This starting point was chosen because one of Kew’s oldest residents is the cycad Encephalartos altensteinii in the Palm House, which was brought to Kew in 1775 but probably started growing before the Linnaeus classification system was even devised.

Kew was founded in 1759 by Princess Augusta, the wife of Frederick. Prince of Wales. The 300 acres (132 hectares) of gracious parkland owe their survival amid the spread of the smart London suburbs to their status as a royal park and favourite leisure ground so that, once botany became a proper science, Kew was ready to receive it. It proved an ideal home. The concept of the Botanic Garden, part public park, part scientific research facility, was born. Its descendants have sprung up all over the world, forming a unique network of botanical research institutes mapping, describing and researching plant life on earth in all its variety and splendour.

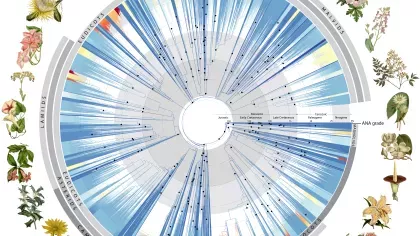

Today there are more than 300 scientists at the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, from taxonomists who identify and name plants and fungi to systematists who undertake comparative studies between and within plant groups, to plant conservationists, plant health experts, and researchers whose work spills over into politics, policy and economics through the study of land use, plant-insect interactions, plant natural capital and food.

Some of the science, of course, has changed beyond recognition in the 250 years since Kew was founded, with rapid advances in the understanding of, for example, molecular biology, and the technology to exploit it. But often the questions scientists have been trying to answer have remained pretty much the same.

The first plant scientists were genuine pioneers. Often they worked against prejudice and indifference. Botany wasn’t regarded as a real science. At best it was seen as a Cinderella discipline, fit for gentlemen amateurs and ladies of leisure, dabbling in their gardens. Most great botanists started out as something else, gardeners or engineers, sometimes even monks and priests. They were seen as eccentrics, their company tolerated on expeditions of conquest and discovery (as Joseph Banks was on Captain Cook’s first voyage), but no more.

There are some remarkable characters among these frontier scientists, and stories of triumph and of tragedy. Some, of course, found themselves barking up the wrong tree, or even scraping at the wrong bark. But the real characters are the plants themselves, from the orchid that looks like a bee to the waterlily big enough to sit a child on. They exerted a powerful fascination that has inspired at once a quest for knowledge about their science, a cultural interest in taming, growing and (often) eating plants from the furthest corners of the Empire, and a passion to understand these compelling curiosities.

A great scientist once said that the important thing is not simply to accumulate facts, but to ask challenging questions and to seek to answer them. Some of the greatest challenges on earth today – climate change (and, in particular, increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide), population growth, food security and disease are intimately connected to our symbiotic relationship with plants and fungi.

Plants and fungi will certainly provide at least some of the solutions to these issues. The terminology and the scale may have changed: we can probably afford to believe that we will never again allow an entire country to starve because of lack of understanding of genetic diversity (as happened in Ireland in the 1850s when potato blight destroyed the Irish potato crop), at least not in Europe. But in the historical scientific literature it is remarkable how often we find long-dead scientists asking the same questions we are asking today: What plant and fungal diversity occurs on Earth and how is it distributed? What plants (and where) do we need to conserve to safeguard against ecological scarcity and environmental risk? Which plants and plant characteristics enable resilient and sustainable landscapes in the face of disease and environmental perturbations? How do plants and fungi contribute to natural capital and sustainable livelihoods and how do we manage them?

This is a story that is still going on. There may not be quite as many grey beards and waistcoats as in the days of Kew’s first botanists, but the scientists are still here. Joseph Hooker and George Bentham would surely have been deeply satisfied that their passionate belief in the importance of plants, and their ideas about how to learn from them, are still at the heart of what Kew does today.

We need those ideas more than ever.