Filling in the gaps: seed collecting for the future

Sarah Cody explains how gap analysis is helping our partners collect the seed of crop wild relatives (CWR) for a project called 'Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change', run jointly by Kew's Millennium Seed Bank and the Global Crop Diversity Trust.

Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change

Climate change is one of the biggest challenges facing modern agriculture and the predictions for increasing temperatures and changes in rainfall pose a big threat to global food security. In response to this global threat, Kew’s Millennium Seed Bank Partnership has joined with the Global Crop Diversity Trust to launch ‘Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change: Collecting, Protecting, and Preparing Crop Wild Relatives’.

This project aims to safeguard the wild relatives of important crop species so that important characteristics are conserved and can be used to improve our crops, breeding in new characteristics to make them more suited to future climates.

Crop vulnerability

Crop plants are especially vulnerable to rising temperatures and climatic change. Unlike animals, they cannot get up and walk away from a stressful environment. They are rooted to the ground and, for the most part, are dependent on humans to collect and sow their seed to complete their lifecycles. Because of the domestication process many of our crops are low in genetic diversity and in great danger of being wiped out by pests, diseases and environmental stresses such as drought, flooding and higher temperatures.

Crop wild relatives (plant species that are genetically related to crop species but that have not been domesticated) can contain far greater diversity than their domestic cousins and so may hold increased potential to adapt to crop pests and diseases, adverse weather conditions and longer term changes in climate.

Resilience

One way to improve the resilience of our crop plants is to harness the genetic diversity found in their wild cousins. By introducing CWR into breeding programs, the useful traits they contain, such as high yield and disease resistance, can be passed onto our crops.

Teaming up with the Global Crop Diversity Trust, Kew scientists are supporting countries around the globe in the collection of seeds from the wild relatives of 29 of the most important crop plants, including banana, apple, sunflower and sweet potato as well as crops like sorghum, cowpea and millet, which are staple foods for many people in the poorer parts of the world.

Targeted seed collections for plant breeding

The project focuses on collecting the seeds of plants which are not too distantly related to the crop, ie wild cousins that have retained their genetic diversity and which have a good chance of being successfully crossed with the crop to produce fertile progeny. For the 29 crops in this project the inventory of close crop wild relatives stands at ~450 species.

The first generation of a cross between a crop and its wild relative is unlikely to lead to the perfect supermarket-ready crop. The progeny may have inherited disease resistance or other valuable characteristics from its wild parent, but it will have also inherited many undesirable traits that can only be tamed though repeated back-crossing with the cultivated parent.

This can take years, which is why we need to collect these seeds as soon as possible so we can pass them onto specialist plant breeders (pre-breeders) to start the process of creating new crop varieties that are adapted to climate change.

Gap analysis and the importance of Kew’s collections

In order to make quality seed collections we need to know the geographical distribution of the target species and where the gaps in our seed collections occur. To achieve this another project partner, the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), is employing a powerful method called gap analysis. This uses location data on herbarium specimens coupled with knowledge of current seed bank holdings to help us prioritise the species and locations of crop wild relatives that are in most need of collection.

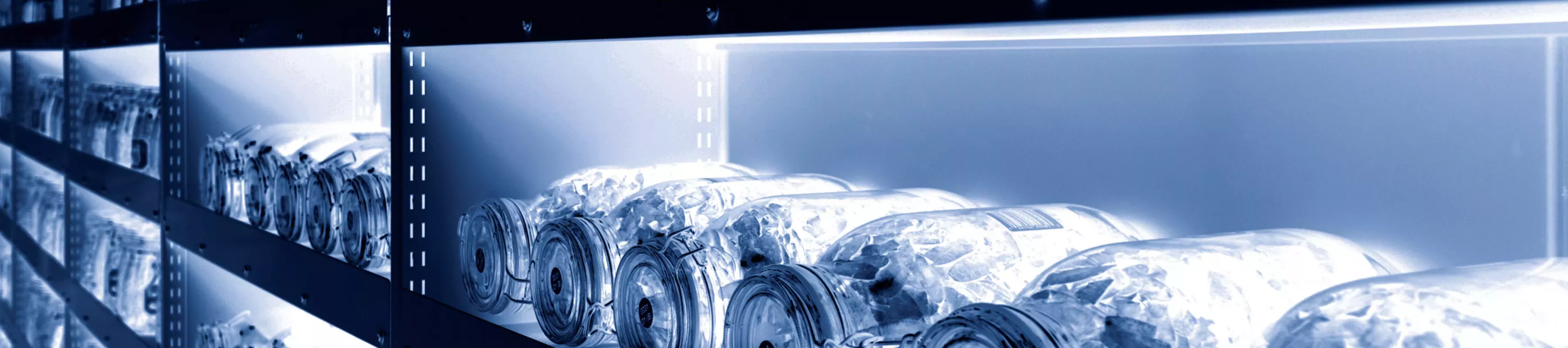

Kew's collections include over 7 million herbarium specimens, such as the specimen of cowpea below, and 5 billion seeds collected from over 40,000 species. The data associated with these collections have been combined with data from other herbaria, genebanks and experts worldwide, and this information is vital to the gap analysis.

Mapping and modelling

Herbarium specimens are a valuable record of a plant species in time and space. Fortunately for us, botanists since the 1700s have fastidiously noted down information about their specimens, such as the collection location, the soil type, the climate of the area, the altitude, and other potentially useful information, such as the local name of the plant and how the plant is used by the surrounding community. Today, with the benefit of technology we can use this information in many useful ways and gap analysis is just one of them.

The scientists at CIAT used location data from the herbarium specimens of crop wild relatives to map the places where these plants were originally collected. Then, through climate modelling they were able to extrapolate the data to make predictions of where other populations of the same species are likely to grow. This tells us the expected geographic range of the species and this is then compared with global seed collection data, including that stored in Kew's Millennium Seed Bank, so we can identify priority locations for seed collection.

The Crop Wild Relatives Global Atlas

The map below shows the gap richness of all the high priority species for all crop genepools combined, and shows which geographic regions around the world are in the greatest need of collecting. South Africa, the Mediterranean, the Near East and Southeast Asia are areas which have high numbers of priority species that we still need to collect. The full results of the gap analysis can be found on the Crop Wild Relatives Global Atlas on the Adapting Agriculture to Climate project website.

The task ahead

The reality is that many crop wild relatives are poorly collected, and in almost all instances the collections held in gene banks across the world do not represent the full geographic range of the species. This puts crop wild relatives, and therefore our major food crops, in a very vulnerable position, especially since many are threatened in the wild and in danger of going extinct.

The good news is we are now supporting partners across the world to collect their CWR, and thanks to the use of gap analysis we can now focus our resources on the highest priority species and where to collect them in order to fill in the gaps.