5 September 2023

The botanical artist who helped uncover the world's biggest waterlily

Botanical illustrator Lucy Smith takes you behind the scenes of Kew's quest to identify Victoria boliviana: the newest and largest giant waterlily.

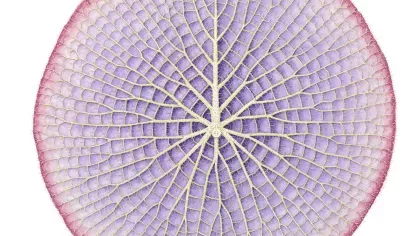

Victoria boliviana, the largest waterlily in the world, was identified in 2022 by a team from Kew and Bolivia.

Detailed observations by Kew botanical illustrator Lucy Smith were vital to the project, although she had never described a new species before.

Drawn from Lucy’s blog, this is the story of how botanical art helped to find a giant, hidden in plain sight.

The art

As a botanical artist, my work usually helps scientists to describe new species – by turning words and observations into clear, informative illustrations. Botanical art also helps us to look closer at the plants we already know.

Inspired by the work of Walter Hood Fitch, a Kew botanical artist who drew and painted giant waterlilies in the mid-1800s, I decided to illustrate the Victorias to understand them more clearly.

I didn’t know what was in store for the future: that in the following years I would be observing a species new to science.

The Victorias

The giant waterlilies of the genus Victoria are found only in South America. For a long time, it was thought to have two species, Victoria amazonica and Victoria cruziana.

Victoria’s flowers uniquely open one at a time, each bud emerging from the depths of the water to the surface. On the first night, they are white and ‘female’, opening just enough to entrap the beetles which pollinate them. On the second night, they dramatically change colour and shape. Now the flower is in its male stage, releasing pollen and freeing the beetles so they can take pollen to another first-night flower.

At Kew, they're grown from seed every year. You can see them in the Princess of Wales Conservatory and the Waterlily House from spring until autumn.

Over five growing seasons, I spent many early mornings and late nights in the Princess of Wales Conservatory trying to capture the open flowers at the perfect point.

The first time was very exciting! Watching and waiting for a flower to open and not knowing exactly when it would happen was nerve-wracking. The silence in the glasshouse was occasionally broken by the splashing of the large fish in the dark waters of the pond.

The mystery plant

Carlos Magdalena, Kew botanical horticulturalist and giant waterlily expert, had long been obsessed with Victoria. His job in Kew’s Tropical Nursery is to germinate seeds and grow baby plants for display in the glasshouse ponds.

Having grown and studied these plants for many years, Carlos was an expert at telling the differences between them. He was intrigued by images spied online of an unusual-looking Victoria in Bolivia – in 2016, the Santa Cruz Botanical Gardens gifted him some seeds of this strange plant.

By 2018, the first baby plant was ready for display in the Princess of Wales Conservatory. It had a shaky start and was threatened with removal until suddenly it began to sprout beautiful, large leaves with a distinctive shape and strongly coloured rims (the upturned edges of the leaves).

The flowers were also different – although it was difficult to say exactly how. For all the Victorias, a flower cannot be spared until the horticulturalists have self-pollinated enough flowers to ensure seed for next year, so it was not always possible to cut a flower for further studies.

In July, I was finally allowed a flower of the mystery plant. I stayed in the glasshouse long after closing time.

The flower took me by surprise by fully opening when I went to make a cup of tea. It faced away from the viewing path, so I had to balance my camera on top of the high wall of the pond. I was always fearful it would fall in!

It was large, beautiful and very different to the others I had seen so far. I began a long night of photographing, dissecting and drawing.

By the end of the growing season I had observed all stages of the flower, from bud to opening. The seeds were much larger than V. cruziana, and had a distinctive raphe (a ridge at the top of the seed).

The investigation begins

The next year, I was finally able to draw a perfect V. amazonica specimen. Now I had all three drawn.

I showed my illustrations to the botanists in the Kew Herbarium, asking: 'do these look different enough to you, and do you think we should try to name a new species?'

Their reactions were encouraging, so Carlos and I decided to try and describe the plant ourselves as a possible new species.

It was both exciting and challenging to be writing my first scientific paper describing a new species. There was so much work to be done to make it thorough and correct.

Our first roadblock was that we couldn’t suggest a new species without first re-defining the existing two species – which were often mistaken for each other, even in scientific papers.

We gathered a team of scientists from Kew and Bolivia, led by experienced Kew taxonomist Alex Monro. Kew’s scientists worked on deep DNA analysis and made conservation assessments, while an experienced scientist from Bolivia confirmed he had collected this species many years ago and shared his knowledge of the specimens in the National Herbarium of Bolivia.

Art meets science

Carlos and I needed as many sources of data as possible to support our argument. We used the plants grown at Kew to observe and measure features such as the rim heights of the leaves, and inform all of the illustrations.

Herbarium specimens let us study details of the plants up close, while hundreds of geo-referenced iNaturalist records allowed us to observe features that were lost in a pressed specimen. We created distribution maps and wrote detailed descriptions of all three species.

I was used to working on scientific papers, but now for the first time, it was up to me to direct the content. I put my watercolour illustrations on hold and switched back to pen and ink, which I’ve used for over 25 years to help other taxonomists describe their new plants.

The more I drew, the more we learned. As I drew the buds of all three species, I noticed that the parts surrounding the flower’s ovary were a unique shape for each species. We also discovered new ways to tell the flowers apart by the differences in prickles on the outer tepals.

A new waterlily is born

Almost four years to the day after the mystery plant first flowered at Kew, our paper was published in Frontiers in Plant Sciences. Finally, we did it.

It was a hugely intense and exciting day. The large amount of press coverage meant that hundreds of visitors came to the Gardens that day just to see the new species on display. All the team at Kew spent the day giving interviews and filming with the media.

In the Princess of Wales Conservatory pond, Victoria amazonica and Victoria cruziana flanked the new species, onto which a brand-new plant label had been placed: Victoria boliviana.

I took a quiet moment to slip into the Gardens and visit Victoria boliviana to soak up the buzz. It was so wonderful to see members of the public getting so excited, justifiably, about the wonderful new species.

And remember Walter Hood Fitch? The specimen he drew was stored in Kew’s Herbarium. After 177 years, it’s now proven to be the oldest known specimen of Victoria boliviana.

You can see some of my paintings of all three species and a life-sized illustration of a Victoria amazonica leaf in The Wonderful World of Water Plants at Kew’s Shirley Sherwood Gallery until 17 September. I may have had to put my watercolours on hold for a while, but I believe the diversion was worth it.