23 August 2018

The fever tree: help us transcribe a bit of history

PhD Student Kim Walker provides an introduction into a plant sourced anti-malarial medication, Kew’s Cinchona collections and asks for your help…

Not just a bitter taste

Quinine is an alkaloid extracted from the bark of the Cinchona, or ’fever’ tree (Cinchona spp.) and if you’ve ever had a gin and tonic, you will be familiar with the bitter taste of the tonic which is provided by quinine. While it is now mainly used to add a flavour to the nation's favourite tipple, the Cinchona tree bark once held a place as one of the most important drugs in history. Cinchona was discovered in the 1630s as a treatment for malaria and, for 350 years, was the only effective cure known in Europe until synthetic replacements were developed in the 1940s. Malaria remains today one of the deadliest diseases known throughout the tropics, but up until the 20th century the disease was prevalent throughout Europe, including Britain.

The Cinchona tree is native to the eastern slopes of the Andes with a range across Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia, and was virtually inaccessible for most Europeans during the 17th century. Once the bark became an established medicine, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries, demand started to outstrip supply. Threats of overharvesting and the desire to control the source of this precious bark drove various competing empires to source this plant for themselves. Understandably, the Spanish, who were in control of this area of South America, actively tried to prevent this, but failed to establish successful plantations themselves. A race to source and cultivate Cinchona ensued, and eventually both the Dutch, in Indonesia, and the British, in India, founded government controlled plantations for the mass production of quinine.

Sourcing the best medicine

Leading up to the founding of these plantations, Kew and other institutions such as the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, collected Cinchona specimens to try to understand the botany and chemistry of the tree. This was so they could source the best medicine and target the most potent species for cultivation. Cinchona has a complex history involving difficult stories of empire, colonisation and transplantation, and my work at Kew will uncover some of these stories.

My PhD project traces the stories of Kew’s Cinchona bark collections and how they reflect the development of Cinchona as a medicine in the 19th century. Initially I started with the 1,000 specimens held in the Economic Botany Collection at Kew, but have since found more in the herbarium.

Wanted: transcribers

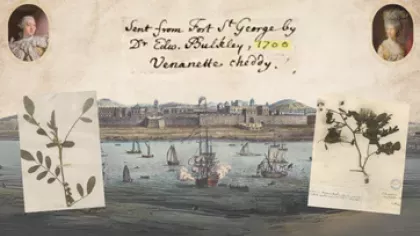

I have recently discovered that some of the Economic Botany bark specimens were originally linked to Kew’s Cinchona herbarium specimens, but these links have been overlooked with the passage of over 200 years. So, as projects often do, I am expanding my data set! There are approximately 1,000 of these herbarium specimens and thankfully, Imogen Makey, BSc student, Geography at Royal Holloway and Madison Johnson, MA student, Cultural Heritage at University College London (UCL), have been working hard on getting the barks and herbaria databased and imaged. However, there is still more work to do and this is where you can get involved.

The herbarium images will be uploaded to DigiVol, an online crowdsourcing platform. Each specimen has handwritten labels with details on locations, collectors and species, and members of the public are warmly invited to help in transcribing these. Sign up is free and easy - see the 'related links' at the bottom to get transcribing.

This work is vital, not only for myself, but for others too. Because of the demand for this tree in previous centuries, many of the forests where the Cinchona grew no longer exist, and so tracing the origins of the herbarium will allow researchers to understand these changes. In addition, Cinchona has always been a very difficult species to understand. This work will greatly aid botanists, conservationists and others to understand the taxonomy, as well as helping a collaboration with a team in Denmark and Bolivia who are working on the phylogenetic ‘family tree’ of this species using Kew’s Economic Botany barks.

So, if you get a few hours one evening, why not grab a tonic water (my personal favourite is with ice and a slice of grapefruit), or even a full ‘G&T’, and help us to reveal the history behind this important tree.